June 5, 2018

Flash back ten years ago to late 2007 and early 2008. George W. Bush was serving his second term as President. Crocs were in style. The new Apple iPhone supplanted the Blackberry as the mobile phone to own. You could stream Netflix shows on your Roku device. Amazon introduced its Kindle e-reader. And, as we all remember perhaps too well, the subprime mortgage crisis was wreaking havoc on the markets, resulting in the fall of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. The economy was losing hundreds of thousands of jobs each month and the future appeared bleak as the U.S. faced its worst financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930’s.

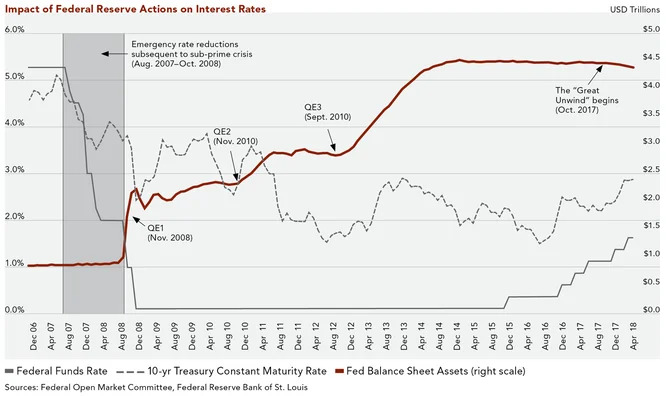

In response to a weakening economy, the Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) took extraordinary monetary policy actions to bring some semblance of stability and liquidity back into the markets. The first “tool” the Fed pulled from their monetary policy toolkit was the Federal Funds Rate. The Federal Funds Rate is the interest rate at which depository institutions (banks and credit unions) lend reserve balances to each other for overnight loans of funds, and represents the cost of very short-term borrowing. Through a series of interest rate reductions during unscheduled emergency meetings, the quick-acting accommodative Fed attempted to both stimulate the economy and stabilize financial markets by lowering the Federal Funds Rate from 5.25% in August 2007 to 1.50% in October 2008—a dramatic difference of 3.75% over a 14-month period (see the shaded portion of the chart below).

While financial markets stabilized due to the sharp cuts in the Federal Funds Rate during this period, the economy still did not respond to the Fed’s efforts to support it. With real interest rates (the amount of interest a saver or lender receives after adjusting for the impact of inflation) approaching zero, starting in November of 2008 the Fed embarked on “Plan B” through the first of three rounds of unconventional “quantitative easing.” Quantitative easing is another “tool” the Fed used to stimulate the economy. By buying up both short-term and long-term U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed bonds, the Fed sought to increase the money supply (the total amount of money in circulation in the country) and bank lending. As a result, between 2008 and 2015 the Fed’s balance sheet grew from $900 billion to $4.5 trillion (see the chart above, right-hand scale).

As the Fed continued to monitor progress toward its dual goals of low inflation and low unemployment, it managed to stimulate the economy and provide liquidity while maintaining a stable inflation range (neither deflationary nor inflationary). About a year after the first round of quantitative easing began, the economy rebounded and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has since grown at a “not too hot, not too cold” Goldilocks rate of approximately 2.2% per year. The Federal Funds Rate remained at a record low targeted range of 0.00%-0.25% for seven years. Recognizing that it was important to gain some amplitude in interest rates so that they would have some ability to lower rates in the event of a recession, the Fed started hiking interest rates again in December 2015. The Fed has raised interest rates five times since then. The Federal Funds rate currently stands at 1.50%-1.75% and the Fed is expected to raise rates at least two more times this year. The Fed has approached interest rate hikes in a gradual and methodical manner, being careful not to raise rates unless the economy is healthy enough to sustain them. The challenge for the Fed remains, as they continue the delicate balancing act of trying to increase borrowing costs enough to prevent the economy from overheating but not so much as to push the economy into a recession.

"Recognizing that it was important to gain some amplitude in interest rates so that they would have some ability to lower rates in the event of a recession, the Fed started hiking interest rates again in December 2015."

We are now at the next chapter in a grand experiment as the Fed begins unwinding years of unprecedented quantitative easing—the “great unwind.” In October 2017 the Fed began allowing billions of dollars of securities on its balance sheet to mature each month without reinvesting the proceeds; the amount of maturing bonds will gradually increase each quarter over the next year. Undoubtedly, this will be a slow multi-year process and may contribute to higher interest rates due to this consequential increased supply of Treasuries. Remember, bond prices and bond yields have an inverse relationship; as prices decrease, yields increase. Therefore, if supply outstrips demand, Treasury prices could potentially decline and Treasury yields increase.

"We are now at the next chapter in a grand experiment as the Fed begins unwinding years of unprecedented quantitative easing—the 'great unwind.'"

Contributing further to supply, recently-passed tax cuts and increased government spending have necessitated the issuance of additional Treasury debt. The Treasury Department is poised to sell an additional $27 billion in new debt issuance, as well as introduce a new two-month Treasury bill later this year.

Demand is another important variable in the equation. During the Fed’s rounds of quantitative easing, foreign demand of U.S. Treasuries remained high and kept downward pressure on interest rates. From 2000 to 2015, foreign central banks bought anywhere from 50% to 80% of all new marketable debt issued by the Treasury. Since 2015 foreign demand of U.S. Treasuries has waned; during the past 12 months, foreign central banks and the Fed bought the equivalent of 18% of new issuance. And, if this past April’s ten-year auction where foreign and international investors’ purchase of just 13% is any indication of this continuing trend, there are growing worries that some of the U.S.’s biggest (foreign) creditors may be stepping aside, just as the Treasury is ramping up sales and the Fed continues its “great unwind.” Continued weakening demand for Treasuries could potentially further boost supply. It remains to be seen whether other buyers will step in or if supply will outstrip demand, putting upward pressure on interest rates.

"During the Fed’s rounds of quantitative easing, foreign demand of U.S. Treasuries remained high and kept downward pressure on interest rates."

Just how much control the Fed has over interest rates through its monetary policy is debatable. The yield on the ten-year U.S. Treasury bond briefly breached the 3% level intraday in April 2018—a level not seen since 2013—and is breaching it again at the time of this writing. In fact, the ten-year Treasury has been hovering in a trading range right around 3% for a few months now. Why does this 3% level matter? Many bond traders consider the 3% level to represent a psychological hurdle, which, if exceeded by a key yet unknown amount, could free interest rates to go higher.

"The yield on the ten-year U.S. Treasury bond briefly breached the 3% level intraday in April 2018—a level not seen since 2013—and is breaching it again at the time of this writing."

Let’s consider the impact raising rates might have on various players in the economy.

WHAT DO HIGHER INTEREST RATES MEAN FOR THE U.S. GOVERNMENT?

For the government, higher interest rates will result in higher interest costs, as interest payments currently comprise 37% of the discretionary portion of the U.S. budget deficit. As interest rates creep higher, the interest on interest payments could increase exponentially, further increasing the deficit.

WHAT DO HIGHER INTEREST RATES MEAN FOR BUSINESSES AND CORPORATIONS?

For businesses, higher interest rates mean higher borrowing costs on loans. Coupled with a record 17-year low unemployment rate of 3.9% and possibly higher inflation, higher interest rates could result in higher labor costs and higher inputs for costs of goods. Business spending may decelerate if it is too costly to borrow to grow and expand. Poorly executed capital ventures, mergers and acquisitions may prove to be costlier if they are made with leverage during an environment of higher interest rates.

WHAT DO HIGHER INTEREST RATES MEAN FOR CONSUMERS?

It depends. For pensioners, higher interest rates would mean higher savings rates and, perhaps, more disposable income, which may help boost the economy. Higher interest rates could translate into higher coupon rates and reinvestment rates for bond investors. Savers would also benefit, but it is highly unlikely they will see Certificate of Deposit rates approach 18% any time soon, as they did in the early 1980’s. Conversely, it is equally as unlikely that borrowers of credit would experience the high double-digit credit card rates of that same era. While interest rates have inched higher, they are still at relative historical lows and the “great unwind” will be a slow and steady process. For home borrowers, higher interest rates will translate to higher mortgage costs. Spenders may see higher prices on goods and services as corporations and businesses try to push their higher labor and goods costs through to the buyer.

WILL THE “GREAT UNWIND” LEAD TO HIGHER INFLATION?

It remains to be seen whether the “great unwind” and its corresponding increasing interest rates will have an inflationary effect on the economy. A bustling economy will foster higher domestic demand as well as higher imports, both of which could possibly have an inflationary effect. Trade tariffs and higher oil prices may fuel inflation as well.

However, other factors stemming from demographics, technology, and globalization may serve to dampen inflation. As an increasing number of Baby Boomers retire from the work force, their younger counterparts, who typically earn lower wages, will replace them and minimize wage pressures. Technology and innovation have improved productivity and lowered the costs of goods and services, putting a lid on inflationary pressures. The recently passed tax bill may motivate corporations that are benefiting from lower taxes to increase spending on technology, boosting productivity and muting inflationary pressures further. Global competition has given businesses the flexibility to suppress wage pressures, as they are able to source low-cost labor from abroad. If we experience inflation, its practical impact will depend on the degree of influence held by the multiple factors at play, the impacts of which often counterbalance each other.

"If we experience inflation, its practical impact will depend on the degree of influence held by the multiple factors at play, the impacts of which often counterbalance each other."

The only thing that is certain is that there will be uncertainty. This equates to higher volatility in both credit and equity markets. We recommend a defensive posture in the face of heightened volatility. To achieve this, we suggest that interest rate sensitivity be minimized in bond portfolios. Additionally, balanced portfolios of stocks and bonds ought to be constructed with enough equity exposure to earn sufficient returns to beat inflation in order to preserve purchasing power. As always, we advocate maintaining a high-quality, diversified portfolio and a long-term perspective.

Download Article: The Great Unwind