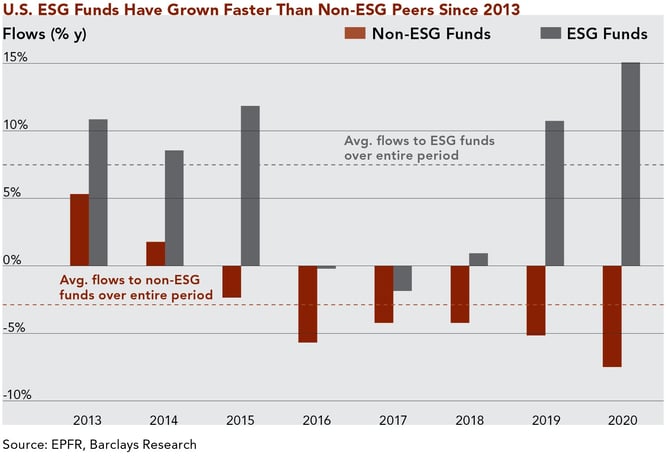

It’s no secret that ESG (Environment, Social, Governance) investing is more than a passing fad. ESG investors select companies with a focus on how the business impacts the environment, manages relationships with employees, customers, partners, and communities, and maintains fair and transparent corporate governance. These criteria matter to the investing public, which over the past several years has voted with its wallet. In fact, in the U.S., ESG-focused investment funds have attracted more new inflows than non-ESG funds every year since 2013. Decision-makers across the industry, from allocators advising pension funds to individual investors, are increasingly demanding that their investment managers incorporate ESG considerations into their processes.

ESG investors often consider performance as a secondary objective to aligning their portfolios with their values. A common refrain is that average to slightly below-average performance will suffice, as long as the portfolio is comprised of companies leaving a positive environmental and social impact in the eyes of the investor. However, there doesn’t have to be a choice between investing for long-term returns and investing in ESG-friendly businesses.

The concept of ESG investing has existed for decades. In the 1950s and 1960s, several multi-employer pension funds made investments in housing projects and medical facilities to promote social good. In 1980, presidential candidates Reagan and Carter promoted social considerations for allocating pension dollars. The SRI (Sustainable, Responsible, and Impact) Investing Conference was founded in 1990. There were over 150 socially responsible mutual funds in 2001. So why the recent rise in ESG’s popularity? As with several other paradigm shifts, multiple factors are contributing. One is the growing national conversation around issues like climate change and the wealth gap. Another is the rise of ETFs, which has led to the creation of numerous ESG-focused funds available to the average investor, albeit with lucrative fees for the manager. Yet another might be generational. With Generation X and Millennials more likely to review their portfolios for ESG impact, it follows that new contributions to their retirement nest eggs are more likely to be allocated with ESG considerations in mind.

Fortunately, those that want strong portfolio performance and those that want the businesses in which they invest to benefit multiple stakeholders are often speaking the same language. The common thread is durability.

The most valuable businesses are also the most durable and sustainable. A basic cash flow analysis shows why. If the value of a firm is the present value of its future cash flows, the first few years don’t matter very much. Real investor wealth starts to build when companies can produce year after year of growing cash flows far into the future. The market decides which businesses are enduring by assigning them higher valuations, and vice-versa. Print newspaper companies might generate strong current cash flow, but their days of trading at rich valuations are over.

Further to technological obsolescence, what else might impair a business’s durability, and therefore its value? ESG analysis attempts to answer this question by asking whether stakeholders other than shareholders stand to lose in the future. The durability of a business model can be called into question if one or more stakeholders (e.g. suppliers, customers, employees, or the community) is consistently being hurt. There are examples everywhere. A manufacturing firm that treats labor poorly can suffer from sub-optimal productivity and a reduced ability to attract talent, which can erode its competitive advantage. Satisfied employees treat customers better, and turnover is expensive. A mortgage broker that puts customers into the wrong loan in order to get a deal done may soon run out of customers. A coal mining firm that doesn’t consider the community or the environment may accelerate adverse regulatory responses or competition from new technologies. Each of these situations describes a direct hit to business durability through poor treatment of a stakeholder, and each is value-destroying for shareholders.

Sound long-term investment processes seek to uncover durable business models. It follows that the analysis of any company for inclusion in a long-term portfolio necessarily involves the analysis of whether, and how, multiple stakeholders benefit. At Clifford Swan, we believe that one of our jobs as fundamental investors is to examine the whole “ecosystem” around a company to determine whether it contains elements that might disrupt the business model in the future. Accordingly, much of our work will overlap with that of ESG-focused investors.

If all of a company’s stakeholders win, then each has an incentive to grow the firm and keep its foundation strong over time. With all parties aligned, rewarding long-term investments can be found without sacrificing what matters to ESG investors.

Download Article: Long-Term Investors Cannot Ignore ESG

The above information is for educational purposes and should not be considered a recommendation or investment advice. Investing in securities can result in loss of capital. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance.