August 21, 2018

We can only either spend or save the income we receive. And, since you can’t take it with you, income that is initially “saved” must eventually be “spent” through bequests, both charitable and non-charitable (heirs). Some spending is not discretionary, such as tax, medical, housing, food, utilities, and other living expenses. Income less this non-discretionary spending is available for further spending or saving. Charitable giving is funded by discretionary income or savings. Therefore, to understand how charitable giving could be influenced by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, we need to look at how the law will impact discretionary income and savings.

THE BASICS

ESTATE (AND GIFT) TAX EXEMPTION

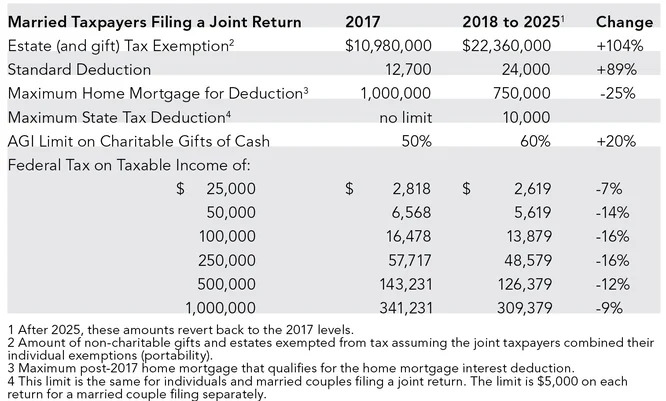

In 2017, lifetime gifts and estates less than about $5.5 million were exempt from gift/estate tax. Married taxpayers combining their exemptions could exempt $10.9 million. These exemptions more than doubled in 2018 when the gift/estate tax exemptions are $11.2 million and $22.4 million, respectively.

Charitable giving was not subject to gift or estate tax in 2017 and still is excluded under the new tax law. Although a specific gift/estate tax benefit from this charitable exclusion is harder to realize given the significant increase in the gift/estate tax exemption, less gift/estate tax will be paid increasing the amount available to “spend” through charitable, or non-charitable, lifetime gifts and estate bequests.

STANDARD DEDUCTION VS. ITEMIZED DEDUCTIONS

Turning to income taxes, a taxpayer may either itemize their deductions or take the standard deduction that has almost doubled (89%) from 2017 to 2018. Married taxpayers filing a joint return with 2017 itemized deductions of no more than $12,700 would not itemize and therefore not get any particular tax benefit for their charitable giving itemized deduction. In 2018, this “joint return” threshold is $24,000. The 2017 and 2018 standard deductions for individuals are half of these “joint return” amounts.

Typical itemized deductions include home mortgage interest, state and local income and property taxes, and charitable contributions.

- The 2017 limit on the value of a home mortgage qualifying for an interest deduction was $1 million. In 2018, this limit was reduced to $750,000 for post-2017 mortgages. The related “lost” home interest itemized deduction, assuming a 4% interest rate on a mortgage acquired after 2018, is at most $10,000.

- There was no limit to the amount of state and local income and property tax (SALT) payments that could be included as an itemized deduction in 2017. In 2018, the SALT itemized deduction is limited to $10,000 for individuals and married taxpayers filing joint returns. The limit is $5,000 per return for married taxpayers that file separate returns.

- In 2017, a taxpayer could deduct up to 50% of their adjusted gross income (AGI) for cash contributions. In 2018, that AGI limit increases to 60%. The AGI limit on gifts of long-term appreciated securities remains at 30% for 2018.

For most taxpayers, it will be more difficult to exceed the standard deduction with itemized deductions in 2018. But, since a taxpayer would only take the standard deduction if it resulted in lower tax, the increase in the standard deduction will reduce income tax and increase the discretionary income available for charity.

Some taxpayers will continue to itemize despite the reduction in their “non-charitable” itemized deductions. In such situations, there will be a direct tax benefit for each dollar of charitable giving up to 60% of their AGI (30% for gifts of appreciated securities).

Taxpayers with large home mortgages and those in high-tax states may experience an increase in taxable income. The possible loss of itemized deductions for home mortgage interest and SALT payments (assuming deductions are itemized) must be compared to the reduction in tax rates to determine the net effect on federal tax and therefore discretionary income.

LIMIT ON HOME MORTGAGE INTEREST VS. REDUCED TAX

The maximum “lost” itemized deduction for interest paid on post-2017 home mortgages is $10,000. This translates into a federal tax increase of between $1,200 and $3,700 depending on the level of taxable income. The mid-range of this increase is $2,450 for joint incomes of $200,000 and single incomes of $100,000. The reduction in federal taxes due to the decrease in tax rates more than offsets the increase in tax from this “lost” home mortgage interest deduction for joint returns with taxable income greater than $60,000 and individual returns with taxable income greater than $95,000.

Although it’s unlikely that a taxpayer will pay more tax in 2018 because of the lost home mortgage interest deduction (offset by the tax rate reduction), consideration must be given to the effect on federal tax of the 2018 limit on the SALT deduction.

LIMIT ON STATE TAX (SALT) DEDUCTION VS. REDUCED TAX RATES

The 7% to almost 15% reduction in federal taxes from reduced rates as applied to a taxpayer’s taxable income (after the standard or itemized deductions) generally offsets the potential increased federal tax from the $10,000 limit on the deductibility of state and local income and property (SALT) taxes.

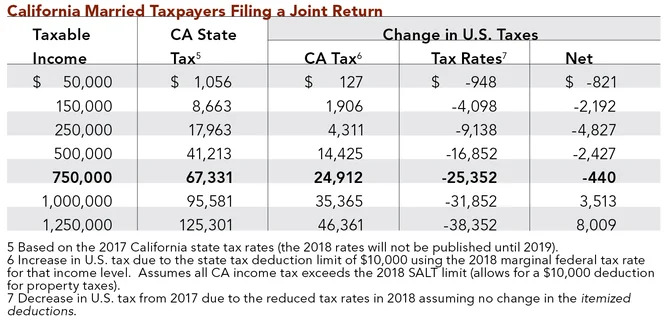

Even in a high-tax state like California, joint taxpayers with taxable income of less than $750,000 will pay less federal tax due to the reduced rates after the effect of the SALT deduction limitation (see table below). This net reduction in federal tax exceeds the maximum increase to federal tax from the reduced limit on the deduction of interest on post-2017 home mortgages for almost all joint taxable incomes between $75,000 and $400,000.

Taxpayers in other states with lower tax rates will fare better and some will be unaffected by the $10,000 SALT deduction limit. Overall, most taxpayers will have more discretionary (after-tax) income to spend, including charitable gifts, or save.

BUNDLING OF CHARITABLE CONTRIBUTIONS

A simple technique to achieve a specific federal tax deduction for charitable gifts is to “bundle” multiple years of giving into one year. Combining three years’ $8,000 gifts into one year’s $24,000 gift would achieve the standard deduction for spouses filing a joint return. Any other charitable giving, or itemized deduction, would result in a related federal tax reduction over what would be paid using the standard deduction.

GIFTING OF APPRECIATED SECURITIES

The ability to bypass tax on appreciated securities is still a tax benefit of charitable giving. As in the past, the donor values a gift of an appreciated security as the security’s gift-date market value and the donor is not required to recognize any gain from the appreciation on their tax return. Occasionally, a donor will gift appreciated securities and use the cash they would have donated to repurchase the gifted securities in order to achieve a step-up to their tax basis. This tax-avoidance technique is more important given the decline in other tax reduction opportunities due to the reduction in allowable itemized deductions and increase in the standard deduction.

IRA QUALIFIED CHARITABLE DISTRIBUTIONS

There is no change to the Sec. 408(d)(8) IRA Qualified Charitable Distribution provisions of the federal tax code that were made permanent by the Protecting Americans From Tax Hikes (PATH) Act of 2015. Since no income is recognized by the donor, there was never a charitable deduction available.

When a donor reaches the age of 70½ he or she can instruct their IRA administrator to transfer up to $100,000 to a charity each year. Although this transfer qualifies for the donor’s required minimum IRA distribution, it is not included in the donor’s gross income for tax purposes. This $100,000 limit is an annual limit and the donor can transfer $100,000 to charity each year. This limit is also “per person,” allowing the donor’s spouse who has his or her own IRA, if filing jointly, to transfer another $100,000 to a charity each year.

The transfer must be directly from a traditional IRA or a Roth IRA, and the IRA donor cannot take any possession of the distribution prior to it being transferred to a charity. The permissible charities exclude donor advised funds, private foundations, and charitable remainder trusts.

These IRA Charitable Rollovers, that sidestep the charitable deduction issues since they were never taxed as income, will become more attractive. It is like getting a 100% charitable deduction without having to itemize and regardless of what the charitable deduction rules may be at the time.

MORE DISCRETIONARY INCOME AND SAVINGS TO GIVE

Most taxpayers will have more discretionary income or savings to donate in 2018 than they did in 2017. The increase in the gift and estate tax exemption, the increase in the standard deduction, and the lower tax rates will reduce federal tax for most and therefore increase discretionary income and savings available to give. A charitable gift, even after any related tax reduction, is almost always a net financial outflow to the donor. Any related tax efficiencies will reduce, but do not eliminate, the net amount given away by the donor. The decision is what to do with the additional discretionary income and savings since we can’t take it with us.

Download Article: Giving Under the New Tax Law: Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017

The above information is for educational purposes and should not be considered a recommendation or investment advice. Investing in securities can result in loss of capital. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance.