March 21, 2017

The U.S. economy may be at an inflation inflection point. Oil prices have doubled since February of 2016, and the election of Donald Trump as the President of the United States has added stimulus concerns. Expectations of substantial fiscal and tax initiatives could spur additional economic growth and subsequently increase inflation. However, the market is not at a consensus due to various economic cross currents.1,2

A starting point for considering whether inflation is at an inflection point is to review a newsletter article we published in the first quarter of 2010. Titled “The Inflation Contagion: An Analysis,” the article noted that inflation had been low, relative to recent history. Inflation changed materially from 1850 to 2010 (and subsequently into 2016). From 1850 to 1913, inflation was a minimal 0.4%. Following the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913 until the abolishment of gold- and silver-backed bank notes in 1934, inflation increased at a higher rate of 1.5%, suggesting that central bank involvement may have spurred higher levels. Once the U.S. completely converted to a “full faith and credit” paper currency for public use, inflation averaged 3.8% annually from 1934 until 2010 (3.6% overall average from 1934 to 2016).

There are several key concepts to understand before addressing where inflation may head. First, we note that inflation has three components: 1) actual inflation (a backward-looking measurement of reality); 2) expected inflation (inflation that is basically the market’s general expectation for the future); and 3) unexpected inflation (the difference between expectations and reality). As an example of unexpected inflation, imagine if expectations for future inflation are 1.5%, yet actual future inflation turns out to be 2.5%. The unexpected portion of inflation is the 1.0% additional inflation imbedded in that 2.5% (2.5% actual – 1.5% anticipated = 1.0% unexpected). Actual inflation, expected inflation, and unexpected inflation are quite dynamic, and what people perceive as happening is in constant flux. Finally, there are a number of economic forces that help to create unexpected inflation, which are discussed below.

The second concept we need to understand is: how does one actually measure inflation, and what, if any, are the criticisms of this measurement? That is, what is inflation and what does it really mean? Most people are familiar with the headline inflation number, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is published monthly by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In particular, the CPI measures the changes in a basket of goods and services month-by-month and year-by-year. Alternatively, the Federal Reserve monitors the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation rate, which is published by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Both have measured average inflation in the 1 to 2% range over the last several years.

However, there is some debate over whether inflation measurements underreport actual price changes. As noted above, the CPI measures changes in a basket of goods and services; how that basket changes is subject to much discussion. One economic expert, John Williams of American Analytics & Research in San Francisco, has filed a number of dissenting public opinions3 in response to BLS open commentaries. He argues that changes in CPI calculations since 1990 have biased the reported CPI numbers downward. The BLS introduced some key theoretical modifications, including substitutionary effects (which impact the specific goods and services in that basket because consumers will substitute one product for another in response to higher prices) and hedonic effects, which typically occur with technology goods (increased quality and/or effectiveness for the same expenditure—e.g. computers). Williams contends that CPI would be substantially higher without these modifications. It might be reasonable to assume that overall inflation is somewhat higher than currently reported.

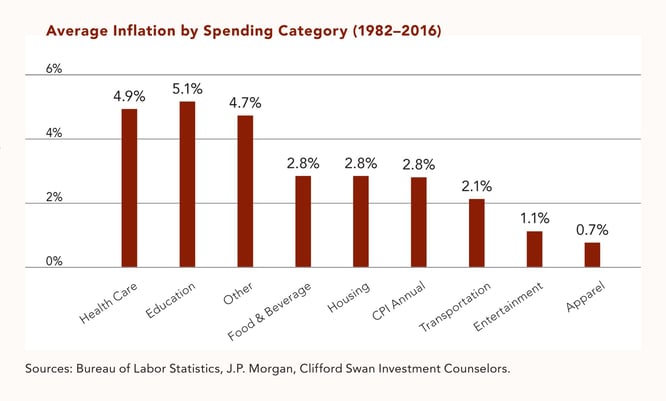

In addition, CPI is a general spot estimate of inflation, and does not measure the same experience for everyone. As the chart below shows, inflation varies by spending category. One would expect the inflation perceived by college students to be different than that of elderly retired citizens. Each group purchases different products and services, each with different pricing influences (e.g., tuition, books, and computers vs. healthcare, food, and utility costs). Perhaps the key focus is the direction that inflation takes, however measured.

With these concepts as a backdrop, what might we expect with inflation going forward? In what direction might it be moving? First, over the last few years, CPI inflation has approached 2% while the economy averaged about 2 to 2.25% annual real growth. With the election of President Trump, if some or all of his proposals on fiscal and tax stimulus are implemented, we might see economic growth approach 3%. Given the very modest slack in unemployed and underemployed workers, there is a reasonable expectation of increasing wage growth. In addition, the demand for commodities may continue to increase, along with the commensurate price increases from that increased demand. If one includes the potential impacts from protectionism and tariffs, the price of domestic goods may also see upward inflationary pressure. Additionally, with the pickup in financial lending, money growth, and increasing interest rates, there are decent reasons to expect higher inflation levels due to monetary factors. So, what are markets expecting now?

Based on the current relationship between the U.S. Treasury 10-year yield and the U.S. Treasury 10-year TIP (inflation-protected bonds), the financial markets appear to be pricing in about 2% inflation over the intermediate term (a stated goal by the Federal Reserve). These expectations are above the roughly 1.4% rate seen just one year ago, but increased recently due to the factors discussed above. Can inflation go higher than 2%? Based on history, it could reach the 3 to 4% level and still be consistent with the eighty year average. In the last 25 years, inflation has been in the mid-single digits (3 to 6%). So, to ask again, could inflation go higher? Yes. And, there lies our possible inflection point.

Counter to this point, there are a number of financial and economic forces that are working against increased inflation. The high debt levels in the U.S. and around the world may exert a deflationary drag as people and governments attempt to reduce the growing debt levels. In the U.S. alone, we have seen a doubling of debt over the last eight years, from $10 trillion to roughly $20 trillion. Also, there is significant production capacity around the world. For example, in China, the steel industry is exhibiting excess capacity. Increasing levels of production may lead to lower prices.

However, keep in mind that heavy debt levels have multiple implications on financial and economic outcomes. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s recent book4, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, reviews 800 years of financial world history. The results of their historical analysis suggest that elevated debt levels are strongly associated with higher inflation. In an earlier paper5 by the same name, the authors “[found] that the same issue arises in the analysis of high inflation...the government’s gain to unexpected inflation often derives at least as much from capital losses that are inflicted on holders of long-term bonds.” The key takeaway may be that governments can decrease the burden of their debt by inflating their currency, and thereby reducing the real value of the debt. This might be a reflection of the old adage, “There are three ways to deal with government debt: increase taxes, decrease expenditures, and/or inflate the currency.” Inflation could be a critical feature to reducing the burden of debt going forward, given the high U.S. debt level and increasing deficit, and a disinclination to raise taxes and cut expenditures. Tellingly, some have described inflation as a “stealth tax,” as it decreases the real cost of debt over time.

So, are we at an inflection point? Clifford Swan believes we are, but the arguments in both directions appear convincing and have a valid set of bases. Therefore, a reasonable approach might be to hedge those expectations. If inflation could indeed increase another 1% over the next several years with a modest possibility of returning to the 1.5% expectation level, then owning some investment options to counter inflation might be prudent. However, if inflation cannot get much past the current 2% level, the value of these inflation-protection investments is minimal, at best.

In the CSIC article cited above, some of the investment options noted include U.S. Treasury TIPS, commodity funds and commodity-based companies, as well as manufacturing companies that have reasonably good pricing power as inflation increases. However, some of these options, such as commodities, have other risks that can arise apart from inflation, and which make them a difficult hedge. Nonetheless, many of these still remain potential options.

In the end, the question is, “what direction is inflation taking?” While the conclusion might not be overwhelming, there is a reasonable chance of inflation increasing modestly over the next several years. The 2010 Clifford Swan article anticipated 2 to 3% inflation by the mid 2010’s and 5% or more by the end of the decade. We see that 2 to 2.5% level today, and foresee inflation levels rising modestly higher. While we are always vigilant on critical economic trends, it is sometimes easier to see inflection points in the rearview mirror.

1. Durden, Tyler. 2017 Will Be the Year of Inflation. www.ZeroHedge.com. 14 December 2016.

2. Blitz, Steven. Inflation Won’t Take Off in 2017. www.barrons.com. 21 January 2017.

3. Williams, John. No. 515- Public Comment on Inflation Measurement and the Chained CPI (C-CPI). www.shadowstats.com. 8 April 2014.

4. Reinhart, Carmen, and Kenneth Rogoff. This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton University Press, 2009.

5. Reinhart, Carmen, and Kenneth Rogoff. “This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly.” National Bureau of Economic Research, No. 13882, March 2008.

Download Article: Inflation: Is This the Inflection Point?